CAR T-Cell Therapy: How It Works

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is an investigational form of immunotherapy — in fact, the first gene therapy — if FDA-approved. CAR T cell therapy is offering promising options for patients and clinicians who are struggling with refractory cancers that do not respond to, or are ineligible for other standard options, such as surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or bone marrow transplant.

There are 3 main types of lymphocytes (white blood cells) that have action against cancerous tumors:

- B cells

- T cells

- Natural killer (NK) cells

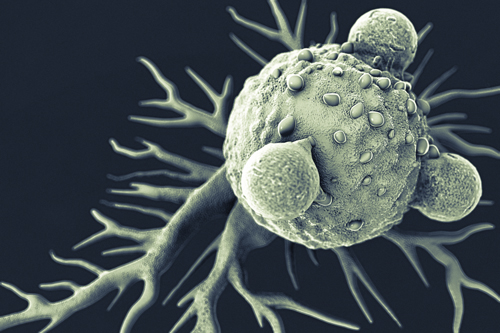

CAR T-cell therapy works with the patient’s own immune system to help boost the cancer-killing effects of the T lymphocyte. Normally, T-cells have a direct killing action on cancer cells and also communicate with the immune system via cytokines — cell signalling molecules. However, cancer cells can evade the T lymphocytes. The T-cells become less effective, have low proliferation, and don’t recognize cancer as a foreign body.

CAR T-Cells: Getting Aggressive on Cancer

Simply put, CAR T-cell therapy is a biomedical engineering feat.

The patient’s own T-cells are modified to recognize tumor antigens and attack the cancer cells. What kinds of cancers are CAR T agents treating?

Aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma is a malignancy with promising, advanced research. One CAR T-cell agent currently under FDA review for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is Kite Pharma’s axicabtagene ciloleucel (KTE-C19), with data from their ZUMA-1 trial for this condition.

Leukemias, such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), have also shown extended remissions in studies with CAR T-cell therapy. Yong and colleagues also report on evolving research involving CAR T-cells directed against solid tumors like:

- Glioblastomas (brain tumors)

- Liver cancer

- Breast cancer

- Lung cancer

- Pancreatic cancer

CAR T-Cell Therapy: A Living Drug

CAR T-cell therapy involves several steps:

- First, blood is taken from the patient via leukapheresis to collect the lymphocytes. The T cells are then isolated.

- Next, the T cells are genetically engineered in the laboratory to produce chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) — a protein — on their surface. The genes are inserted into the T cells using an inactive virus. This process leads to the CAR T-cell that recognizes the cancer antigen on the targeted tumor cell.

- The engineered CAR T-cell is then grown in the laboratory for about 2 weeks to produce billions of more cells. The cells are frozen and sent to the hospital where the patient will undergo treatment. The patient receives chemotherapy to kill off some of their white cells prior to infusion. This helps the body to better accept the CAR T-cells.

- The CAR T-cells are re-infused into the patient where they continue to multiply, seek out, and attack the tumor target antigen. CAR T-cells remain in the body after infusion and can continue to function. In investigational studies, some patients have been able to maintain long-term remissions possibly due to this effect.

CAR T-Cell Therapy: The Structure

What are CAR T-cells? CARs are fusion proteins that contain 3 distinct functional domains:

- The first domain is an antibody fragment, also called a target-binding domain, that elicits signals to activate the engineered T cells to recognize and bind to target antigens on the surface of the cancer cell.

- The second component, called the costimulatory domain, allows the CAR T-cells to proliferate and survive.

- The third domain, called the essential activation domain, activates the CAR T-cells.

Many different antigen targets are under research; however, the most common antigen that has been targeted in lymphoma and leukemia trials is known as “cluster of differentiation 19” (CD19). CD19 is expressed on the surface of most B cells, both healthy and cancerous. CD19 is not found on other healthy cells, and therefore those cells are not targeted by the engineered CAR T-cell. B-cell aplasia is reported as an expected side effect, and can boost the risk of infections, but has been managed with intravenous immunoglobulin replacement.